Alvaro Mutis, celebrated Colombian-born poet and novelist, dies in Mexico at 90

Alvaro Mutis, a celebrated Colombian-born writer who drew on his lifelong wanderings to create the character of Maqroll the Lookout, a modern-day philosophizing, seafaring adventurer, died Sept. 22 in Mexico City. He was 90.

His wife, Carmen Miracle, told the Mexican media that the cause was a cardiorespiratory ailment. An expatriate not unlike his fictional hero, Mr. Mutis had lived for more than five decades in Mexico.

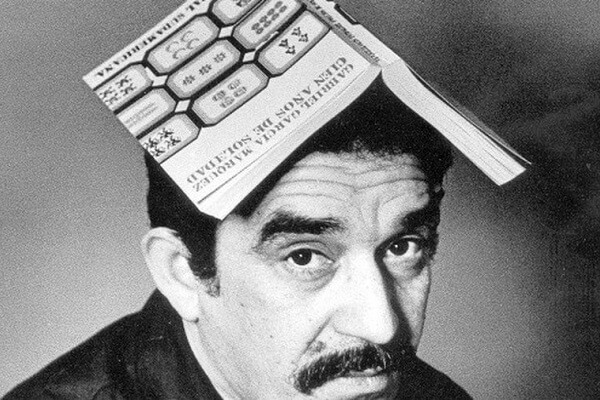

In the Spanish-speaking world, he was considered a towering figure of Latin American letters. Gabriel Garcia Marquez, the Nobel Prize-winning Colombian author, once described his friend Mr. Mutis as “one of the greatest writers of our time.”

About the world of Alvaro Mutis and Gabriel García Márquez

Mr. Mutis was credited with imbuing his poetry and fiction with the evocative sensuality, mysticism and imagination that characterized many of the most lauded works in Spanish-language literature.

By the end of his life, Mr. Mutis had received prestigious literary honors including the Prince of Asturias Award and the Miguel de Cervantes Prize. But for years he had gone undernoticed in Latin America — and almost entirely unnoticed elsewhere — as he pursued a workaday, if successful, business career.

He worked in Colombia as a public relations manager for Standard Oil and later in Mexico as a sales manager with 20th Century Fox and Columbia Pictures. Among other curiosities, he provided the voice-over for the Spanish-language version of the TV crime drama “The Untouchables.”

Mr. Mutis sold re-run broadcast rights in Latin America to programs such as “Punky Brewster,” “The Mary Tyler Moore Show,” “Diff’rent Strokes” and “Fantasy Island.”

He once remarked that he wrote his early works “under the most absurd circumstances — hotels, airports, bars” — until he retired from Columbia Pictures at 60.

“Without this rambling career,” the novelist John Updike wrote in the New Yorker magazine, “how could he have supplied the eerie wealth of maritime and dockside details, the delirious abundance of geographic and culinary specifics, that give fascination and global resonance to his novella-length tales of Maqroll?”

Maqroll — whose name was intended to reveal no particular nationality — was born in one of Mr. Mutis’s early poems. The character grew into a full-fledged literary hero through his appearances in novellas: tales that included such escapades as a jaunt through a Peruvian gold mine, management of a brothel and an encounter with a tramp steamer.

His works were known to English-language readers mainly through the translations of Edith Grossman and most notably “The Adventures and Misadventures of Maqroll,” which was published by the New York Review of Books in 2002.

That volume contained seven novellas, translated as “The Snow of the Admiral,” “Ilona Comes With the Rain,” “Un Bel Morir,” “The Tramp Steamer’s Last Port of Call,” “Amirbar,” “Abdul Bashur, Dreamer of Ships” and “Triptych on Sea and Land.”

Writing in the publication World Literature Today, Grossman described Maqroll as “a knight errant with a duffel bag over his shoulder and a watch cap on his head, whose only home is the road he travels.”

Mr. Mutis said that he dubbed Maqroll “El Gaviero,” or “the Lookout,” in homage to the maritime works of Joseph Conrad and Herman Melville.

“For me, a lookout at sea embodies the image of the poet,” he told the publication Americas in 2004. “He is the one who sees farther. After all, what is poetry? It is that hidden part of man that the poet reveals to the reader. I believe that each poet who completely surrenders to his work is a lookout.”

Alvaro Mutis Jaramillo was born on Aug. 25, 1923, in Bogota. His father was a Colombian diplomat who served as ambassador to Belgium, and many times the family sailed between Europe and Colombia.

The younger Mr. Mutis often visited the coffee and sugar plantation founded by his maternal grandfather and said he was as affected by the land as he was by the sea.

“All that I have written,” Mr. Mutis wrote in World Literature Today, “is destined to celebrate and perpetuate that corner of the tierra caliente from which emanates the very substance of my dreams, my nostalgias, my terrors, and my fortunes.”

Mr. Mutis became involved in literary circles in part through the invitation of the Colombian poet Leon de Greiff. By 1948, Mr. Mutis and a friend had written a chapbook of poetry, titled “The Balance.”

Mr. Mutis wrote that all copies of his debut book were destroyed that year in what became known as El Bogotazo, the rioting that followed the assassination of Colombian politician Jorge Eliecer Gaitan. His next volume of poetry, “The Elements of the Disaster,” followed in 1953.

In 1956, Mr. Mutis left for Mexico after becoming entangled in legal trouble stemming from his alleged mismanagement of funds at Standard Oil. At the behest of Colombian dictator Gustavo Rojas Pinilla, Mr. Mutis was jailed near Mexico City for 15 months at the notorious Lecumberri prison until the Rojas Pinilla regime fell.

One of Mr. Mutis’s most noted early works was “Diary of Lecumberri” (1959), a memoir of that period.

“That experience was truly an influence, much more than Conrad or anyone else they care to name,” Mr. Mutis told an interviewer. “Because, of course, in a place like that, one experiences situations which are extreme and absolute. In there the density of human relations is absolute.

“And there is one thing you learn in prison, and I passed it on to Maqroll, and that is that you don’t judge, you don’t say, that guy committed a terrible crime against his family, so I can’t be his friend. No, in a place like that one coexists. The judging is done by the judges on the outside.”

His first work of fiction, “The Manor of Araucaima,” was published in 1973. Jaime Manrique, a noted Colombian writer and lecturer at the City College of New York, described Mr. Mutis’s voice as both “picaresque and profound.”

A complete list of survivors could not immediately be confirmed.

Mr. Mutis said that several times he had tried to end Maqroll’s life during the course of his fictional adventures. The author explained that he could not bring himself to do it: “A French writer said to me once, “Don’t keep trying to kill Maqroll, he’s going to die with you.”

About the world of Alvaro Mutis and Gabriel García Márquez

The two most successful novelists in Colombian literary history, both in the sense of appreciation by critics and in the sense of winning prestigious awards, and being close friends for more than half a century: it is Álvaro. Mutis and Gabriel García Márquez.

About the world of Alvaro Mutis and Gabriel García Márquez

Recently, we published the 2002 Neustadt Award Statement for Colombian writer Álvaro Mutis (s 1923). Here, to help readers learn more about this unique author in relation to Gabriel García Márquez (another famous figure of Latin American literature and the world), we introduce the article by Gerald. Martin, professor of Spanish Language and Literature at Pittsburgh University, USA.

Mutis was born in Bogotá but when he was a child in Belgium, Colombia was always “foreign” in some sense, “strange country” for him. Meanwhile, García Márquez was born in a tropical town with a funny name lying in the middle of a monkey’s neck – as we often call disparagingly – and until twenty-eight, when he Full picture in terms of both art and consciousness, he first came to Europe.

On the outside, the two people are different from each other, and in terms of political views, they seem to be in complete opposite opposites. Mutis was obsessed with what happened before 1453 (“I am completely uninterested in any political phenomenon that occurred after the Byzance Empire fell into the hands of infidel wards”), while García Márquez it is more inclined to events after the Russian October Revolution.

Although he had never been a communist, Márquez was always closer to the communist position in a broader sense than any other ideology throughout his vibrant life.

As Mutis often remarked, one could argue that it is therefore that the couple never talk to each other about politics or literature but point around “la vaina, viejo” (life and big and small consequences). of life) because otherwise they will have little in common, except that both of them are not educated so much: Mutis left school earlier than García Márquez.

Throughout his life Mutis spent most of his time in business, writing only in his “free time,” although it was clear here, “free time” was all the time he did not actually do. salaries, including waiting for an airplane at a remote airport or waiting for bedtime at some unknown hotel.

García Márquez, for the rest of his life writing, sometimes or doing business, is only temporary, reluctant when he is young or as an after-hours hobby in his old age. Márquez is one of the most professional writers in Latin America, and Mutis is one of the least professional. García Márquez eagerly grabbed a computer like a fish with water, Mutis, this is unpredictable.

Mutis is a poet but also writes prose; García Márquez is a writer, loves poetry but does not write poetry. Mutis is a close friend of famous right-wing characters like Octavio Paz; García Márquez does not – his most famous best friend is Paz’s ideological enemy, Fidel Castro.

Literally, both of them share a passion for some literary predecessors: Conrad, Faulkner, Neruda, even Hemingway. But, at first glance, no one said that there was anything in common between the two men about the literary style, literary, aesthetic and literary philosophy.

It is ridiculous to say things like “assuming the sun rises in the west”, but let me joke a bit by saying that it is impossible to imagine the name García Márquez signed under the title Un bel Morir 1, also It’s ridiculous if you imagine Álvaro Mutis as the author of a story like The Great Mother’s Funeral 2.

García Márquez began writing novels and short stories from the age of eighteen, and Mutis, who was only sixty years old, began writing novels, at the age of García Márquez’s office coming to an end. Even so, the two of them are still close friends for over half a century.

After two decades of writing novels, with Hundred Years of Solitude (1967), Márquez became a unique star in the so-called Latin American Boom, the most brilliant period in the calendar. using Latin American prose prose and – without a doubt – one of the brightest “moments” of world literature, meanwhile, surprisingly, Mutis belongs to the “post-boom” period 3 , the anticlimactic period is typical of the postmodern, post-structural and in some sense post-our history, the era of globalization in economics and culture, the era of creation. knowledge and ideology.

Therefore, the contrast between the two is even greater than just the humorous wit that just led above. It can be said that the entire history of Latin American literature separates the two giant Colombians, these two close friends, both masters of the vaina.

Critics and literary historians, whether in Latin America or not, always distinguish two major trends, distinctly in Latin American literature, corresponding to two completely different trends, although obviously related. intimate with each other.

I mean the old-fashioned distinction between literary Latin America itself, literature that focuses on a specific Latin American country or Latin America but generally reflects – in this way. alternatively – the reality in Latin America or the search and discovery of Latin American identity, while the other is the so-called Latin American literature simply because of the birthplace of the author, a writer or has been “European chemistry “(in bad sense) or at least just Latin America by chance because its purpose seems to be some form of universality, which Latin American critics themselves consider to be a disguise for the Europeanization in a frantic way.

By definition, the “Latin American” tradition encompasses costumbrismo 4 of the nineteenth century and most Latin American romanticism as well as a local novel about the land or social novel of the 1920s, even Latin American novels during the “boom” of the 1960s and “fanciful realism” that some of these novels were classified into; the “non-Latin American” tradition includes the nineteenth-century modernism, the twentieth-century pioneerism, and a series of writers in which the most representative is of course Jorge Luis Borges, whom people often refer to when talking about Mutis – in a somewhat superficial way.

Needless to say that Gabriel García Márquez is one of the leading examples of the first view of Latin American literature as it is or should be. In fact, as I said, in many ways, Hundred Years of Solitude is the novel that brought this Latin American literary to the highest point to date, the most homogenous Latin American novel, rolling the novel in which Latin America learns to see itself, the novel that may be for Latin American literature and its maritime astronauts is the same as Quixote for Spanish literature and those Hunt for impossible dreams.

Álvaro Mutis also said the same in an interview with Elena Poniatowska in 1975: “I believe that only García Márquez has captured, successfully achieved and successfully implemented the American world movement. Latin into literature. He alone gave a captivating and accurate view of that world. ”

Not only that. We can add that García Márquez created his own world, Macondo, the world that reminds me of Faulkner’s famous “postage” of Yoknapatawpha, but a world that has traveled around the world. much more than Faulkner’s world, although Macondo only appeared in two of Márquez’s nine novels and three of his more than fifty short stories.

Macondo has now become a shorthand for Latin America’s slow progression or at the same time its poetic “Third World” eccentricities. When a man who is blind and deaf nearly a hundred years old in the Dominican Republic is re-president as the hundredth time, Latin American people just shrugged and said, “Macondo.”

The speech received García Márquez’s Nobel Prize in 1982, The Latin American loneliness only talks about Latin America, the Latin America where fanciful reality and social reality cannot be distinguished from each other, where words not enough to describe the exaggerated nature of everyday experience; while the statement “Lift up the poem” (Brindis a la poesía) of his own on that occasion (received the Nobel Prize) is taken up with the intention of reaching out to greatness that it is completely could be of Álvaro Mutis himself.

This brings me back to the subject of my thoughts. If Latin Macondo is seen under two different literary patterns, like two different mirrors, one straight, one crooked (Bad hour and Hundred years of loneliness), then the “character” (I use This word is not very confident) What is Maqroll of Álvaro Mutis?

Can we imagine Maqroll chatting with Melquíades 7? Is it possible to imagine Maqroll in the context of Macondo? At first, “No” seems to be the most convincing answer. Maqroll, who was born as a literary character in the mid-1940s, even before Macondo was born as a literary place, appeared in most novels and stories of Mutis as well as many of his poems. .

It is the “Guardian” 8, Maqroll el Gaviero, the sea traveler, the adventurer, the wandering wanderer or the “extraterrestrial” (“Maqroll doesn’t belong to any place on this earth”). [Abdul Bashur], whose nickname makes it impossible to think of the Triana sailor, who first saw the mainland in the New World in 1492.

The sailor, like Columbus, was misguided about what he saw and caused the beginning of a series of illusions, the pleasures, the discouragement and the failures that writers recorded over the past five hundred days and days. We now call Latin American literature.

Maqroll is a unique character in Latin American narrative, though he has some not-so-old predecessors in the work of Juan Carlos Onetti, especially the Shipyard (1961).

In addition, it is first thought of the antagonists of Conrad’s character, the consul of Lowry, Juan the Landless (Juan Sin Tierra) of Juan Goytisolo, and other wandering wandering men, real or computeristic. symbol. Mutis himself often tells Malraux’s nearsighted characters and Pessoa’s four poetic characters as reference points with Maqroll.

The difference of Mutis over all is the rational nature of his skepticism – closer to Nietzsche than Schopenhauer, closer to Baudrillard than Foucault – and his unshakable determination in trial and failure, because failure is inevitable.

Maqroll’s origins, nationality, age and form, all of which are blurred, uncertain. Not sure if he is Latin American, at first glance he has nothing to do with Latin American character. Like postmodern literature in general, he is completely non-territorial (deterritoriliazed). Although he speaks Spanish to satisfy the conventions of narrative, we don’t know if he “really” speaks that language.

At times, he was in Latin America, sometimes. The literary lands he once traveled to – never lingering on – were not “earthly” lands, nor fanciful or fanciful.

They remind us of the atmosphere of Graham Greene’s novels, which some critics call “Greeneland”, or even better, “Conradia”, although this call is ironic. At first glance, they are more relevant to what is “real”, a reality unlike the actual 19th-century literature or 20th-century social reality that is a new form of reality and symbolism. or the aliases intertwine into an indivisible body.

The best interpretation of Mutis’s philosophy I have ever met is that of Fernando Cruz Kronfly. He argues that this Colombian writer is one of the few modern modern writers of the 20th century: that most other writers still mourn the loss of this and that, above all else the loss cool the greatest great narrative, the meaning of the sacred history through which Desire, suppressed by Reason – the Reason that once killed God-Father – has bounced back, unconsciously , to force the mind to submit to it.

I believe this is true, but I think there is one additional point. In this so-called postmodern era, when we conduct the creation of all the ideas and ideologies brought by others, all the myths about the origin, all the great narratives, we force must – or be free – choose your identity and understand that meaning is what we assign [to things] and not inherit [from others].

Mutis’s deepest skepticism, as well as that of his character, is at the level of belief itself. Mutis’s special “post-modern” philosophy leads him to a nostalgia for the illusions of old times, but does not lead to the illusion that those illusions still have a chance to exist.

From here, Maqroll’s deep conviction that after all, no better or worse place than any other time or place, and his absolute skepticism about ideologies or events tracing the meaning of the [human] meaning, the conviction is beautifully expressed by Arvaro Mutis himself in Amirbar:

I have never been fascinated by any common myth or esoteric system. I believe that what we inherent within us has given us so many problems, unexplainable places that we do not need to create any more. God, until now, at least in my case, has chosen the simplest and brightest path to show His presence. And if sometimes we can’t see Him, that’s another story.

One of Jorge Luis Borges’s shortest works is Two Kings and their two mazes. The story of King Babylon builds a labyrinth to distract and humiliate other kings, including an Arab king. (“The labyrinth is a scandal, because chaos and wonders are appropriate jobs for God, not people.”).

Thanks to Allah’s help, the Arab king managed to escape the labyrinth and immediately started a war with the Babylonian king, defeating him and taking prisoner. Then the Arab king told the unfortunate prisoner: now he will show him his own labyrinth, a maze without stairs, doors, walls. He tied the Babylonian king to a camel, led him into the desert and left him to die of starvation and thirst, and also died of what we now call “face-to-face” with reality 9.

Mutis, whom Borges shares a few views and preconceptions, is not a man of labyrinths. The labyrinth, in the twentieth century, is obviously meaningless for modernism, where the world is seen as a book; Finding your way through the text towards the ultimate meaning is like finding your way in life, finding Henry James’s pattern on the carpet.

Borges was always interested in playing games where their frivolity was so understandable, while Mutis believed that every maze was truly meaningless; outside they are always desert.

From here the central theme of his, desesperanza, a word, as well as many key words of Spanish (like soledad, sueño), cannot be translated into English, not “desperation”, also not “despair”, but a state of hopelessness, never hope, something like the weak meaning of both words (in English) combined.

And, as Mutis always says, la desesperanza (translating Vietnamese: “great hope”) is more evident in the tropics than anywhere else, although life here is faster, decay is always present, always threatening, always exposed right on the surface of the [perception] experience.

From here, there is a connection [between Mutis] and García Márquez, no matter how different they are. “I met Gabo twenty-eight years ago,” Mutis said in an interview with Alfredo Barnechea and José Miguel Oviedo in 1974: “That night the two of us discussed these topics for the first time. The glare is always permanent in both of us.

Frustration, futile efforts, tropical origin, all present in that first conversation, billowing like a flood, our … The first Gabo meeting was so instantaneous, too effective, too round, because we have the same places, the same obsessions.

And when we talked about Faulkner, we talked about a third common entity for both of us, standing there facing us two. ” In an interview in 1975, Mutis commented that Leaf Storm, García Márquez’s first novel, was “a wonderful novel about the tropics, about losing vitality, losing aspirations.” , lose hope “.

In fact, he made such a claim ten years ago in the essay on la desesperanza (February 1965), in which he placed García Márquez in a tradition that, as mentioned above, includes Conrad, Drieu La Rochelle, Malraux and Pessoa.

In this article he reminds us of “Macondo, where an old colonel who returned from the Colombian civil war waited and waited for it to cancel, waited, but clearly without any hope (with hopelessness, la desesperanza) a letter he knew would never come but it was thanks to the constant and long wait that he could live a life that many years ago had lost all meaning and every possible factor ”.

Mutis continued that novel (Nobody wrote to the colonel, Nguyen Trung Duc’s Vietnamese translation: Colonel waited for the letter – ND) to talk about “the development of fundamental tragedy and innovation. constantly of a person and his most old and private ghosts. ”

He affirmed that the last two pages of this work, with the immortal “End”, are worthy of being included in any collection as a classic of that utterly hopeless, desesperanza.

So in this sense, Macondo is not really a child in Colombia; in fact, as many critics have said, although not with Mutis’s intentions, Macondo is a “state of mind”.

Not Colombia, but the tropics, because the tropics are closer to the desert than most of us ever thought; and the desert itself, in this sense, is only a somewhat less dynamic idea, less flexible than the greatest symbol of being ocean – always different [to yourself], copper Time is always one.

So we see, in a completely obvious sense, Maqroll is always in Macondo. And so we can say, the relationship between Mutis and García Márquez is somewhat similar to the relationship that Mutis recognized between Heyst and Jones in Conrad’s Victory, who is the negative of the other, on both sides of the same ego, as well as the notorious “theologians” of Borges.

Mutis notes that the ruthless thug Jones was stunned “realizing that he had another person with the same identity in front of him but had chosen the other end of the rope anyway.” I will not push this comparison too far, because in the case of Colombian characters, we need to decide who is Heyst who is Jones.

It is almost certain that we will see García Márquez as a good guy who always looks hopelessly in the good of people and believes that in this world in good luck – Mutis is the bad guy. For Mutis, “good people” are almost always bad people because they deceive themselves, but this life should not be built on self-deception.

García Márquez’s lifelong motto can be taken from Gramsci, “Pessimistic intellectual, optimistic will” (Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will).

Mutis would also want to take this motto not from the Marxist Gramsci but from Romain Rolland, whom Gramsci himself borrowed the above sentence, except that Mutis would change it to “Pessimistic wisdom, stubborn will “(Pessimism of the intelligence, stoicism of the will) or even” Pessimistic wisdom, optimistic for the everyday “(Pessimism of the intelligence, optimism of the everyday).

At any rate, the truth is that Alvaro Mutis and Gabriel García Márquez have acknowledged each other all these years, although each has chosen a conflicting polarity of political and literary “rope”; but, when faced with their conclusions and despite their ultimate view of the world, both learned how to “love, work, chat with friends and wholeheartedly committed themselves to the ambush of fate, because they know, not by rejecting those things, but we can avoid the events that make up our lives; they know, only by participating wisely in those things can it draw something very close to a taste of life, a constant of existence, it allows us to live through the day months without having to break their skulls with their conscience. “

In a recent New Yorker review, John Updike wrote one of the most interesting and perhaps most suggestive reviews of the narrative journey of Colombian novelists. However, Updike ends this passionate book review with a complaint:

The lone knights, from Don Quixote to Sam Spade and James Bond, are, in common sense, fighting against bad guys; they give themselves the right to escape practically to engage in the search for justice, the pursuit of constant society.

Maqroll is not; he is one of those rogue wards, “on the sidelines of rules and rules”, and suggests that the bad guys aren’t really as bad as I thought, even if they smuggle, lead a girl and do business. shady around the world. Maybe so, but readers have nothing much to rejoice, in adventures to reach that epic 10.

This is a surprising ending and at first glance is disappointing – indeed a conclusion in which Updike’s conclusion does not seem to fit into his earlier argument of “the dark, selfish character Mutis’s self-deprecating, wise, intriguing, incomprehensible charm ”.

Just like the first Hollywood movies show us this world (perhaps) “as it is”, then disappoints us (or cheerfully) by adding a comforting ending tinged with philosophy or raising the spirit of morality has nothing to do with the plot of the previous paragraph.

However, there is something that deeply satisfies us in Updike’s reaction. If Updike, who is undoubtedly one of the most disillusioned writers of his own fiction, sees Mutis’s point of view – about the bad guys – is depressing, and yet he can’t say no. received (admittedly he tried to expose the inconsistency of that, though not convinced), this only adds to the unusualness in the view of Colombian novelist, a viewpoint absolute disillusionment but above all disillusioned in a previous way like an 11.

——————–

About the author: Gerald Martin is a professor of Modern Languages, teaching at the Spanish Language and Literature Department, University of Pittsburgh. His pre-work includes a review of the work of Miguel Ángel Asturias Hombres de maíz (1981) and El Señor Presidente (2000), Journey through the Labyrinth: Fiction of the Latin American Twentieth Century Latin (Journeys through the Labyrinth: Latin American Fiction in the Twentieth Century, 1989), and some important essays on Latin American literary history in Cambridge History of Latin America (Cambridge History of Latin America, 1985-1995). He now writes a biography of Gabriel García Márquez, a book about Latin American art history, and a book about post-Latin American autobiographical literature Exploding. He was the dean and editor of the Latin American literary series of books by the University of Pittsburgh and a lifetime member of the Twentieth Century Latin American Literary Archive (Paris), and the president of International Institute of Latin American Literature (2000-2004).

Leave a reply